We were all bracing for a crisis.

At the end of 2024, milk supplies were looking a little tight. There was a lot of uncertainty in the market. U.S. dairy herd numbers were already low when the avian flu swept through U.S. dairy herds, and then bluetongue impacted milk production in Europe. We were staring down low dairy herd numbers and worried about herd recovery.

We wondered: with the dairy herd shrinking, would we be facing a milk squeeze in 2025?

Well, that’s not what happened. Instead, 2025 turned into the start of an oversupply cycle.

In this article, we’ll cover:

- Where we are: Prices and production in 2025

- What happened: Why production stayed strong

- Where all that milk is going: Butter, cheese, milk powder and whey

- What’s a dairy farmer to do: Predictions for 2026

Read on for our analysis of where the dairy producers are and where we’re going in 2026.

Where we are: Prices and production in 2025

Right from the get-go, 2025 kicked off with fears about oversupply. Since then, 2025 has seen breakneck milk production and shrinking margins. The U.S. dairy herd size is rising, but the real story is that milk production per cow is up and the percentage of butterfat and protein in milk is also up.

With strong production, there’s milk everywhere: in the United States, across Europe, and in the Southern Hemisphere.

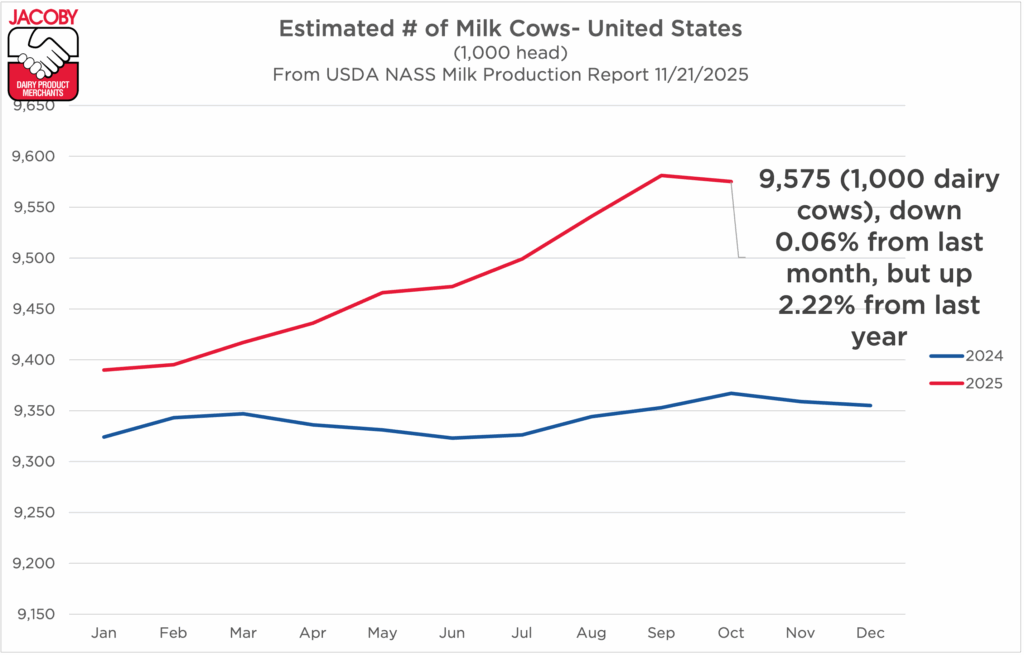

More cows. The U.S. dairy herd size is rising. In the United States, the herd was up in October to 9.58 million milk cows. That’s 208,000 head – 2.2% – more than the same time last year (in the United States as a whole, not just the 24 selected high-production states).

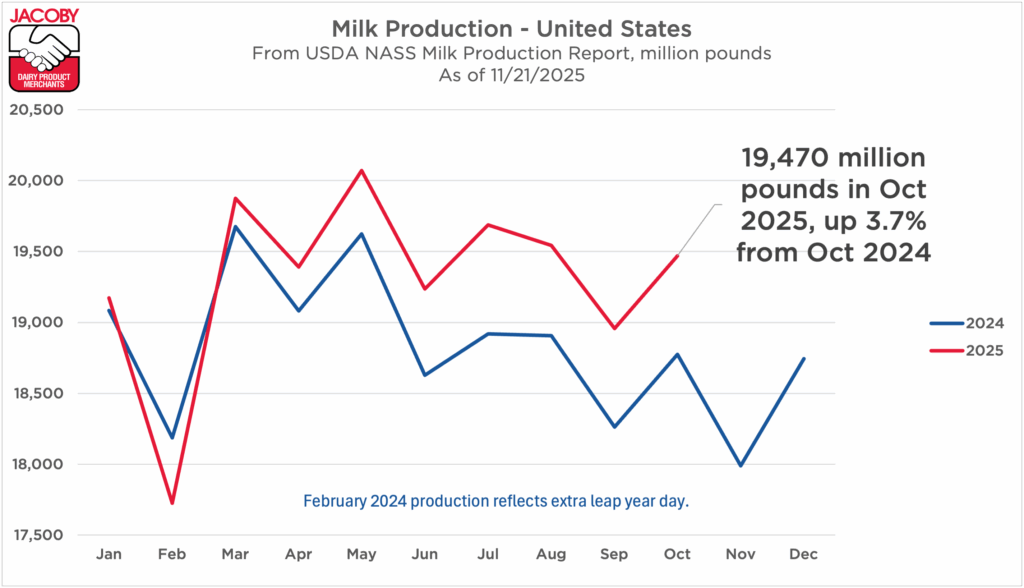

More milk. Total milk production is up 3.7% in the United States in October compared to last year (3.9% if you focus on the 24 major milk production states).

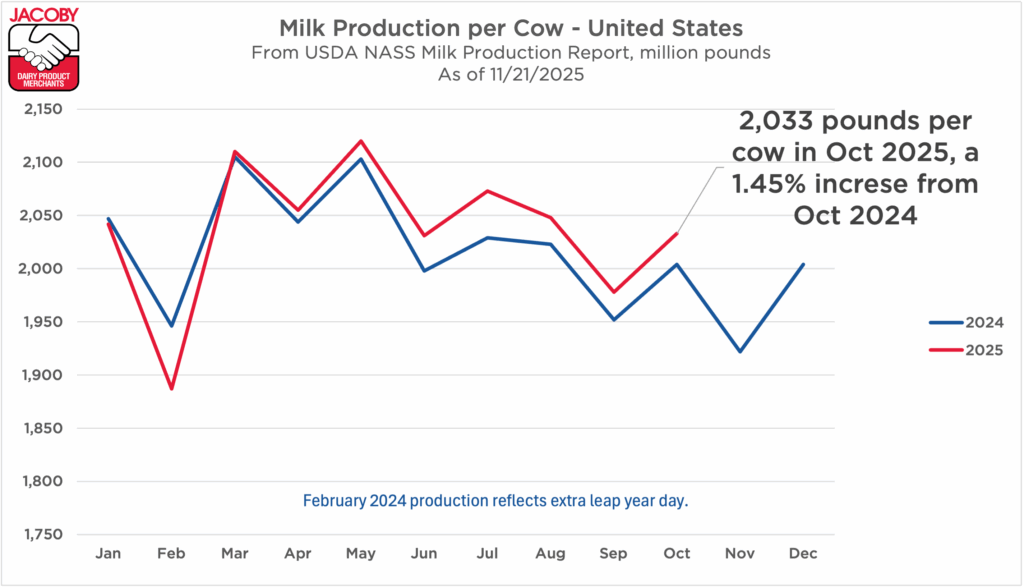

More milk per cow. Milk production per cow is up 29 pounds per cow, up 1.45% in October 2025 compared to October 2024.

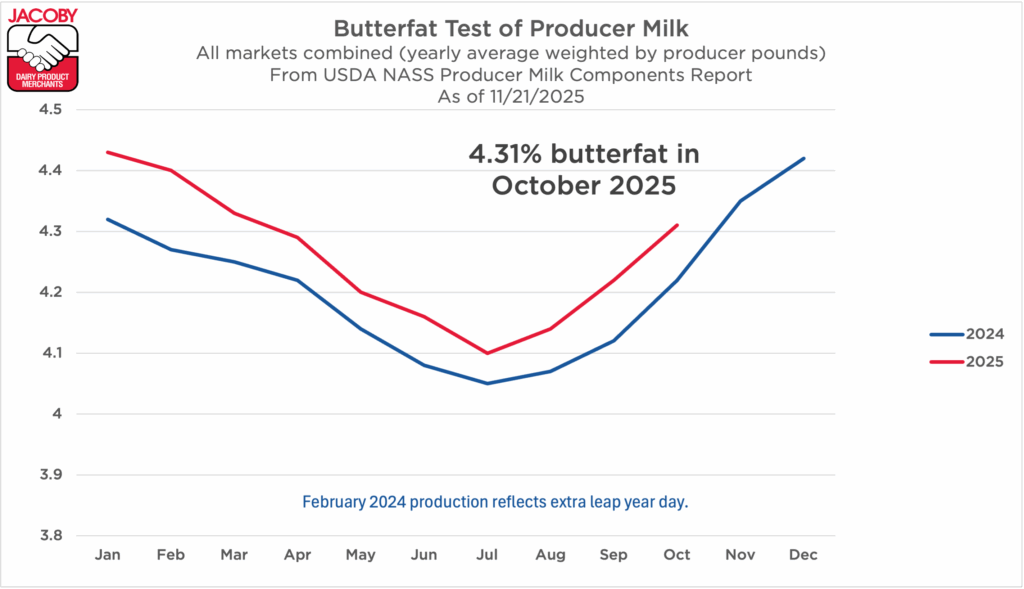

Higher butterfat percentage. The percentage of butterfat in milk is up, with butterfat making up 4.31% of milk components in October 2025, up from 4.22% in October 2024.

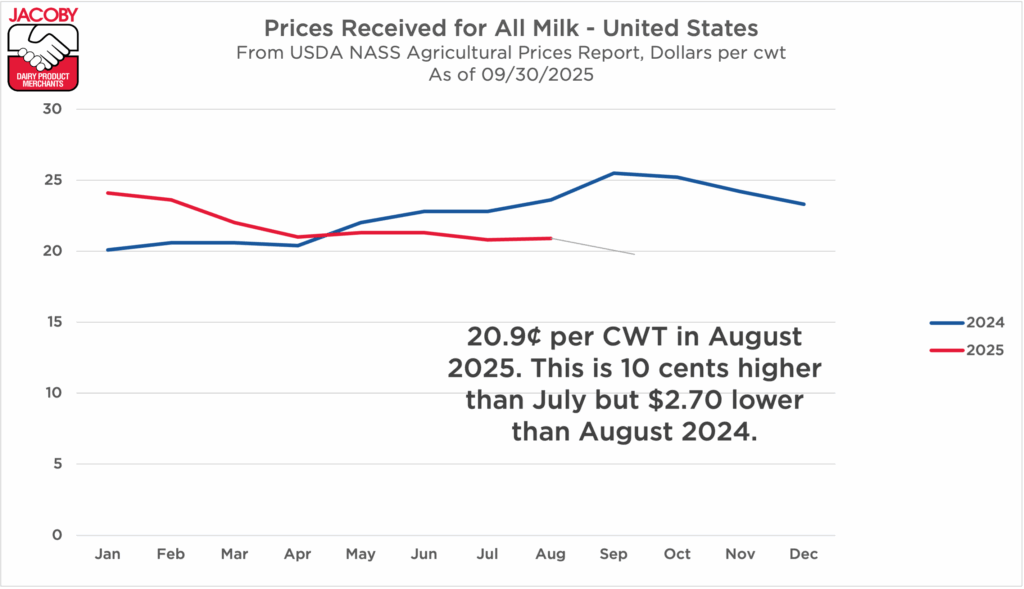

Increased production continues to pressure the market. The all-milk price per cwt is below last year’s level. Milk prices received by farmers have been in decline since August and are expected to continue to do so at least through December.

USDA has not yet published new All-Milk price numbers for September, October, or November But lower FMMO Class III and IV prices assure further declines.

In addition, European production was stronger than expected, with EU milk collection up 5.7% year over year in September.

With milk everywhere, dairy prices on the CME (except for whey) are slumping as high global output and cautious domestic demand keep pressure on margins.

One complicating factor: many U.S. dairy farmers are entering this downturn in unusually strong financial shape. The last two profitable years allowed a lot of producers to pay down debt, and cattle values are roughly twice what they were three years ago. Revenue from calf and cull cow sales is often $3-4 higher per cwt milk sold than just three years ago. That gives bankers more collateral to lend against and gives farmers room to ride out low prices longer than usual, but it also means the exit price for a cull cow has never looked more attractive relative to a $13–$14/cwt milk check.

What happened, and what’s a dairy farmer to do?

What happened: Why production stayed strong

In mid-2023, high feed costs and margin compression all signaled contraction, and cull rates began to ramp up. Many of us feared that there would be a price squeeze in the long run, as it takes time to breed and grow replacement cows.

Instead, a few factors came together to increase production and stabilize and grow the herd.

- Lower feed costs reduced culling – for now. Generally good weather and cheaper corn and forage in 2024–2025 lowered the cost to maintain cows and reduced pressure to cull, helping stabilize and grow the herd. But with Class III and Class IV now threatening to trade in the low-$13s, cheaper feed alone may not be enough to keep cows in the parlor indefinitely.

- Stronger balance sheets and high beef values delayed the supply response. Many dairies used the past two good years to pay down debt. At the same time, cull cows are now worth roughly twice what they were a few years ago, and bull calves are even stronger. That combination has kept lenders comfortable and allowed producers to keep stalls full longer than normal. But once the economics tip, culling could ramp up quickly.

- Better breeding strategies. According to Nate Zwald, president and CEO of Progenco, “sexed semen and the use of beef on dairy cows have all had substantial changes to the genetic progress curve.” Widespread beef-on-dairy genetics increases cow longevity (on average 147 days longer than herds with no beef-on-dairy genetics). Herds using genomic testing, sexed semen and beef semen had heifers more likely to remain in the herd through the first lactation.

- Advances in management practices. Better early life management practices around colostrum, milk feeding, solid feed, and housing can increase herd longevity, productivity, and profitability.

- Breeding and feeding for higher components. In addition to volume, farmers have been breeding and feeding for higher butterfat. They’ve been enriching diets with high-oleic soybeans and supplementing with live yeast to increase milkfat output. Learn more about the butterfat boom here.

Where all that milk is going: Butter, cheese, milk powder and whey

On the price side, the tone has darkened as we move toward 2026.

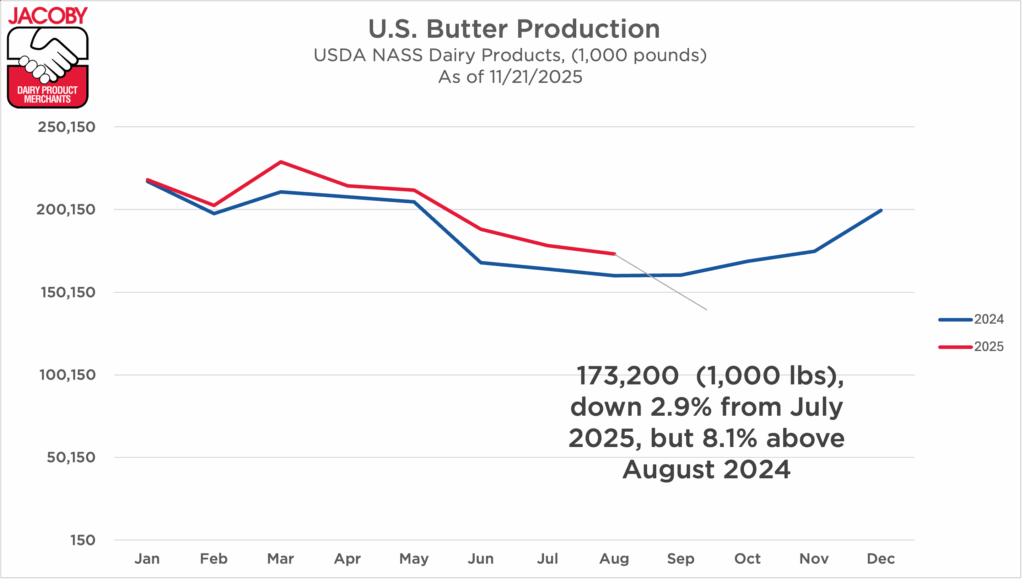

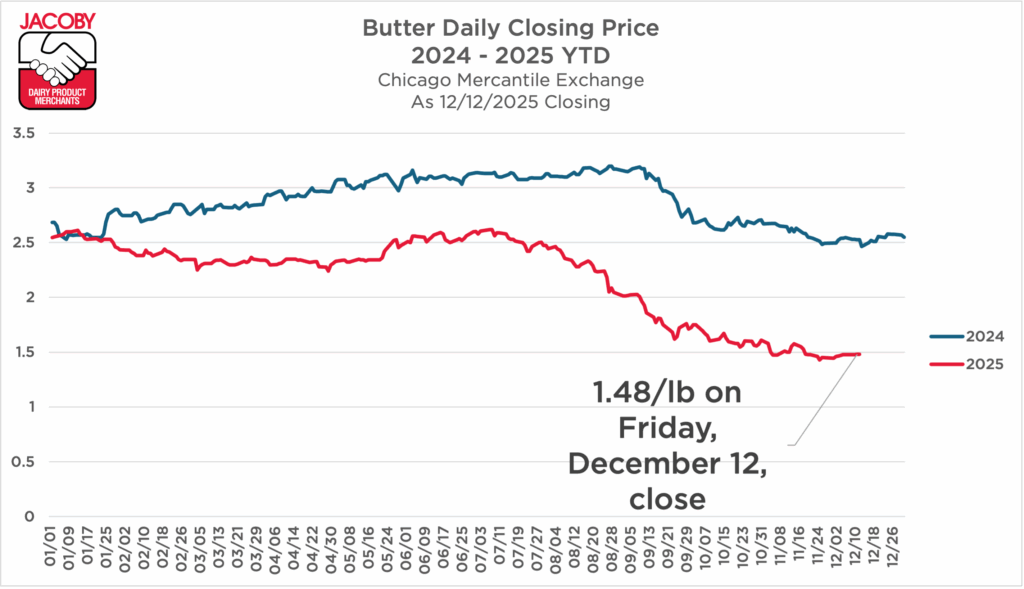

Butter churns are busy, cream is long, and butter production is running well ahead of last year. That’s pushed butter down below $1.50/lb, and we think current levels are more of a temporary floor than a firm bottom. Cream feels roughly in balance today and first-half 2026 contracts are getting locked in. But with additional churn capacity online and another strong spring flush ahead, we still expect very low cream multiples through the holidays and into the spring.

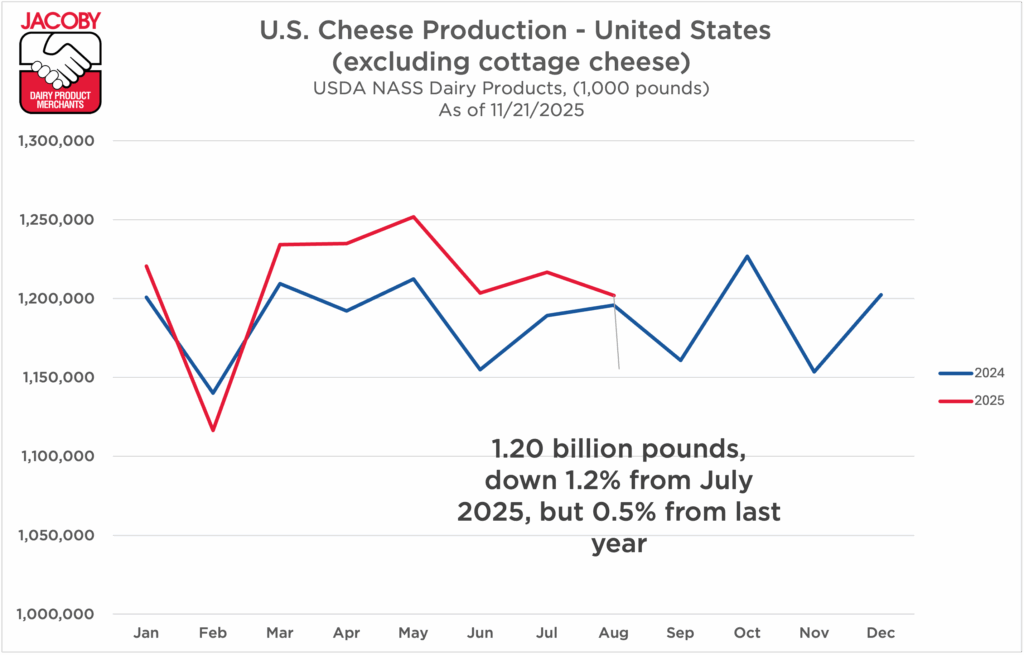

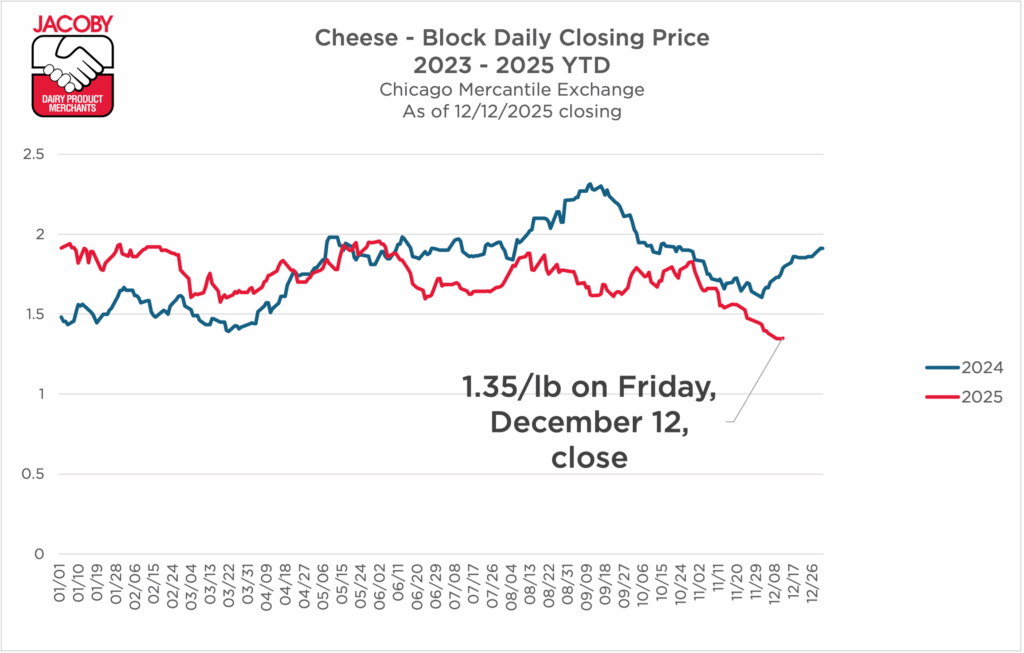

Cheese vats are also full. U.S. cheese production is robust, and exports have had a banner year, setting new monthly records. But with European output and exports climbing, global cheese prices have converged, and U.S. cheese is struggling to find a bottom.

Cheese has already fallen below $1.40/lb, the price many expected to be the floor. Since Class III is driven primarily by cheese, lower cheese translates directly into lower milk prices. Futures still show Class III in the mid-$15s, but at today’s spot values the formula yields closer to $14–$14.25/cwt. In other words: weak cheese = weak Class III, and a $13 Class III is very much on the table.

The pain will not be evenly distributed. Producers in cheese-heavy regions like the Pacific Northwest, California, and Idaho, where pay prices are tightly tied to Class III, are likely to feel the squeeze first and hardest.

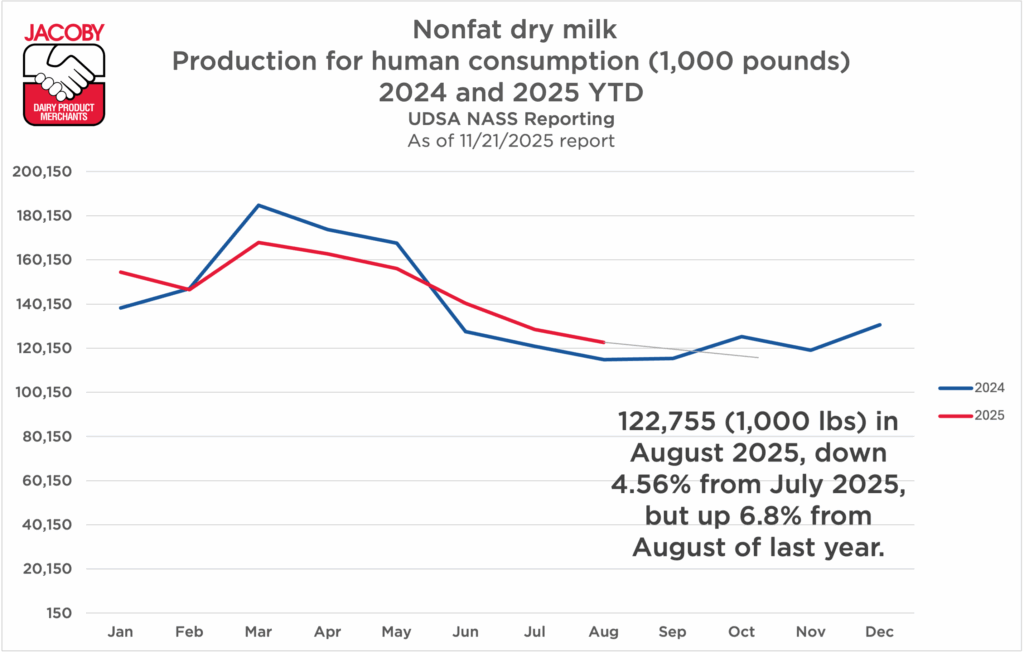

Nonfat dry milk prices have fallen back toward multi-year lows. With inventories building, we’re bearish on NFDM pricing, but we do think there is still more room for storage. We expect dyers to shift toward higher-value protein streams. That may reduce NFDM output and stabilize prices in the medium term.

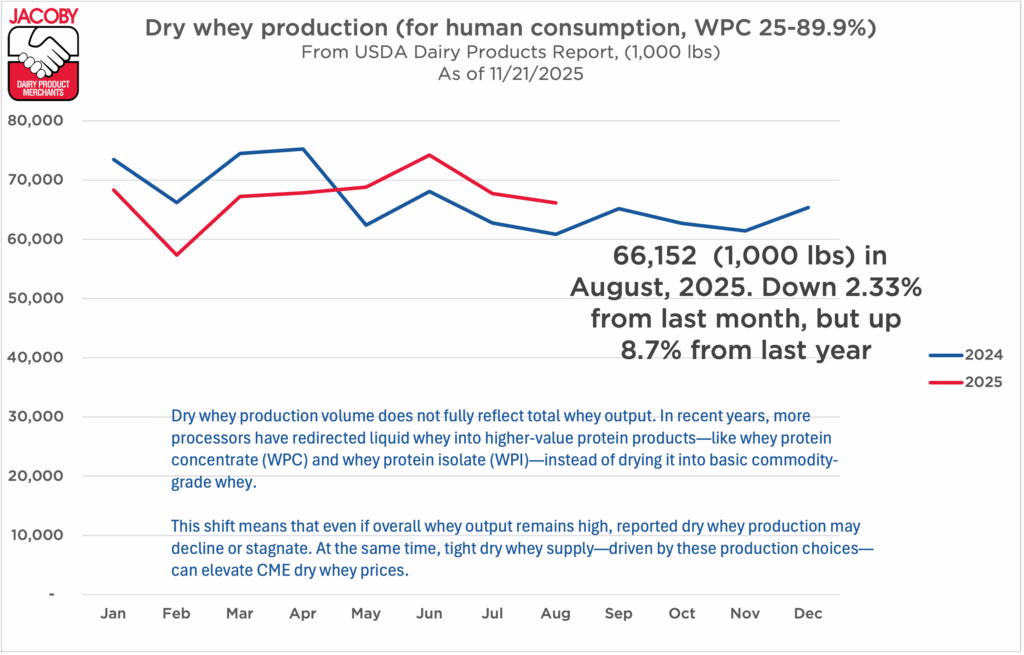

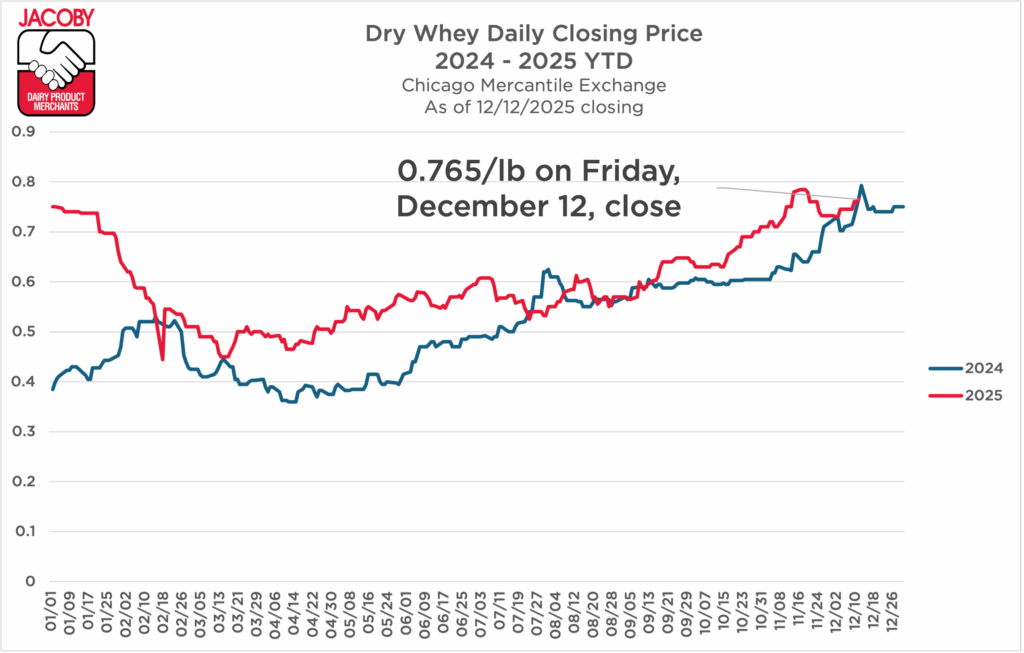

The standout is whey. Demand for high-protein whey products remains extremely strong, and limited raw whey for dry whey keeps CME prices elevated. Whey’s contribution to Class III is roughly a dollar or more per cwt above where it was earlier in the year, making it the rare bright spot in an otherwise bearish complex. The demand for value-added whey protein is currently outpacing supply, forcing those who can’t compete on price to substitute ingredients.

What’s a dairy farmer to do: Predictions for 2026

It looks like things will get longer. With new production coming online in 2026, we think the dairy herd will continue growing and production will continue rising. So, it might be a little while before U.S. farmers start getting more green per cwt from their Holsteins.

With new processing capacity coming online and producers still sitting on relatively strong balance sheets, we think milk will remain long at least through the first half of 2026. The national herd may still creep higher in the near term, but the more important question is when will producers stop filling every stall and start leaving a little more space in the barn?

We recommend a steady hand, prioritizing stable production rather than expansion for the near future.

Dairy farmers take the long view, and that is what is needed now. There are a few hazards on the horizon that farmers could begin to plan for.

Mitigating heat stress

Heat-stressed cattle eat less, which causes their milk output to drop. Heat stress negatively impacts both productivity and milk quality. And unfortunately, the hottest part of the year coincides with the time of year when a cow is typically most productive.

Heat-stress-related damages to production are expected to increase by 30% by 2050. Dairy producers may mitigate heat stress by investing in cooling systems or changing the timing of breeding decisions, since breeding timing impacts when heifers are most productive. Farmers may also consider investments to increase shade. Learn more about strategies for reducing heat stress here (see section 2.1).

Preparing for potential future pathogens

Recent pathogens, like the 2024 highly pathogenic avian influenza A (HPAI H5N1), had a severe and immediate impact on dairy farms. More than 200 herds in 14 states ultimately tested positive for H5N1. During the outbreak, U.S. dairies had an estimated 7% decline in milk yield during and around the time of the outbreak.

We don’t know what the next pathogen will be that hits dairy farms, but there are some steps that farmers can take that may help them be prepared. New research on how H5N1 spread suggests the virus was spread through the udder and mammary glands, suggesting that greater biosecurity in the milk parlor and in raw milk handling are critical ways that milk producers can reduce pathogen spread of H5N1 and possible future pathogens.

Additionally, farmers can plan for movement controls and testing. During the 2024 H5N1 event, USDA issued a federal order limiting interstate movement of dairy cattle and requiring a negative H5N1 test from an approved National Animal Health Laboratory Network lab before lactating cows could cross state lines. Future pathogens are likely to bring similar requirements, so it’s worth stress-testing your replacement, culling, and heifer-movement plans now.

Conclusion: We’re betting on the dairy farmer

Looking ahead to 2026, we don’t see a quick snap-back in prices. We are very bearish on prices for the next 6-12 months. We see more cows, more milk per cow, more butterfat and plenty of product to move. The problem is that producers worldwide responded aggressively to last year’s tightness and higher prices, and supply overshot the mark.

That means pressure on prices even as costs keep creeping up. It also means the producers who stay focused on efficiency, components, cow comfort and risk management will be the ones still standing when the cycle turns.

There are real hazards on the horizon: heat stress, new pathogens, policy shifts, substitution away from dairy proteins and shifting global demand.

But none of those are reasons to panic. They’re reasons to plan.

Milk markets will swing. Costs will rise and fall. Pathogens will come and go. But if history is any guide, you don’t bet against the dairy farmer.

Contact us. We’d love to help you move your milk or improve your purchasing plan.